Basma

Returning home and reaching out to the world

My name is Basma, I am 23 years old and I’m from the north of Shingal, from a village called Borek, near Snuny. I live with my family. There are eight of us in one house.

I graduated from the English language department at the Catholic University in Erbil. Now I am an English teacher to primary school aged children, I also give two online classes in the afternoon and I am myself taking two courses at night.

I love writing, both stories and essays, reading, listening to music and I also love nature.

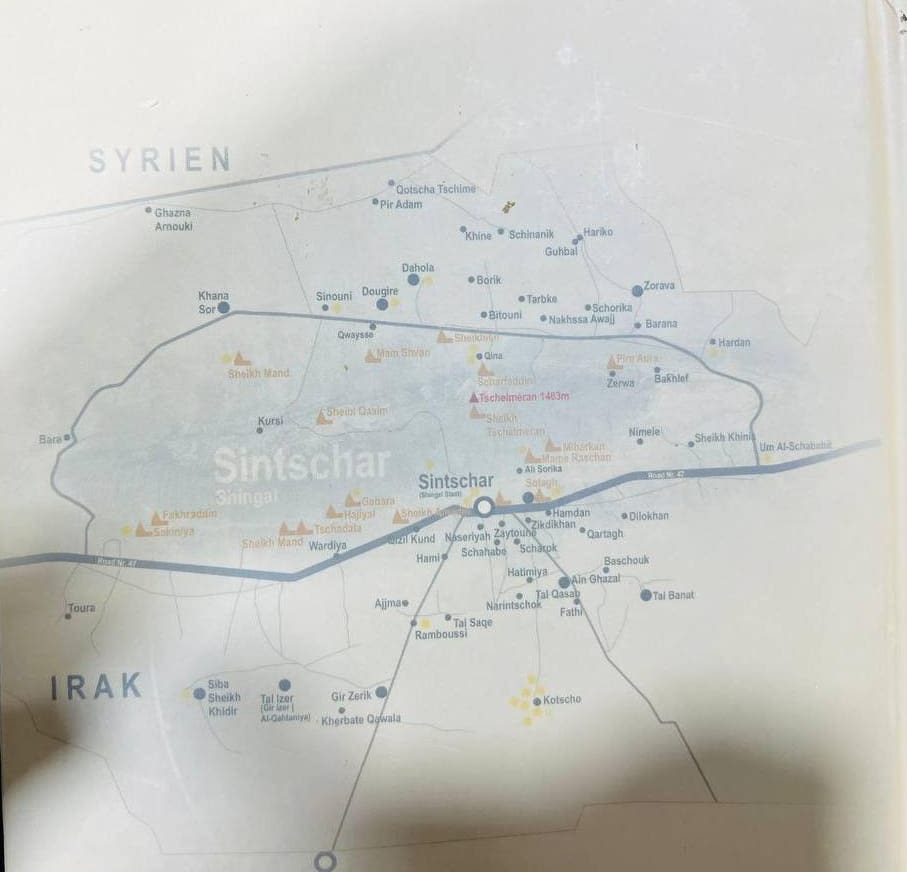

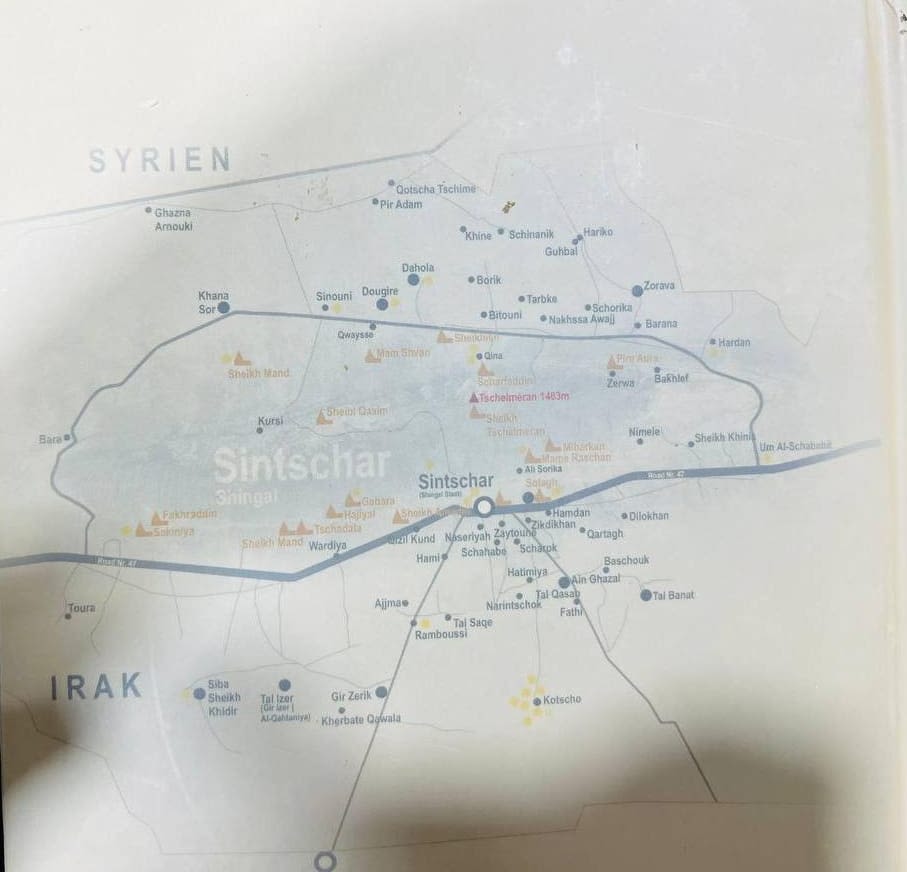

I was part of a multi-faith group who participated in co-writing a book initiated by the Berlin-Potsdam University in Germany alongside the Catholic University-Erbil, Tishk University and Salahuddin University. The book contained a map of Shingal that I helped create. The book celebrates the cultural and religious diversity in Erbil and across Iraq. I was invited to co-present the findings in Germany in 2021.

Transnational connections

This book is where I will start to tell my story. Through it, I've had wonderful experiences and learned a lot.

It's called Ferman 74, which documents the genocide of the Yazidi people by the so-called Islamic State, beginning with the attack on Kocho on August 3, 2014. It includes over 200 survivor interviews and analyses on various aspects of the tragedy. My contribution to this book was creating the Map of Shingal with the authors.

I worked on it during my second year of University with a group from Germany. I helped with the making of a map of Shingal. I gave them all the details about the villages, and where they are located. Here is a photo of the map I worked on.

Additionally, I participated in another project, "Religious Diversity in Erbil," which documents all religious communities in Erbil. These projects involved mostly the same group of people and allowed me to travel to Germany for the publication and completion of both works.

I went to so many places in Germany during those fifteen days. I went to Sans Souci Park, to Potsdam City, to Berlin, to the Brandenburger Tor, and to Hamburg. I visited some of my relatives there. I was re-united with my cousin who I had not seen for around seven years, and my aunt after nine years.

When I look at this book, I remember so many experiences...

Here is my university in Erbil. It all started from here, by working on that project. This is the yard and the entrance.

On the side of the bookshelf is my desk, where I learned so much. I met so many people just online, and I feel that I really know them. They helped me with my writing, and I was helping them too. So we were all working together.

It made me think about my house, and those days when I was working online.

I drew a tent from when we were in the camp. I was working in the tent as well, and I remember one day I was writing in the tent, but there was so much noise around me. Living in a tent is hard. Because of the noise, I couldn't focus on my writing and that used to upset me, and I end up closing my laptop and giving up.

I remember the days where I gave up on writing. I just couldn't focus.

Simple hard life

Before 2014 we lived a simple life. Our houses were made of mud, families relied on farming and produce from their own green patches. My family are farmers, and we had orchards and we depended on the produce for living.

People also had sheep and other animals. Although life was simple, it was a hard life. There was no electricity most of the time, we had around two hours per day of electricity. We were buying water. The water available was not good for drinking and cooking. In fact, until 2022, there was no water in all our villages. Food supplies were scarce and most items were cut off from us by the Government.

Mosul city was struggling too. From time to time, anxiety ran high due to lack of security. In 2013, my brother was studying in Mosul University, but he had to come back and leave his education due to the deterioration of security, fighting and bombs were becoming features of the everyday and as a Yazidi student the anxiety was compounded by the discrimination against Yazidis in predominantly a Muslim city like Mosul. ISIS were also in Syria, and this placed Shingal in the middle between two very bad situations.

Before the events in August 2014, we lived a carefree life, I was a child in my final year of primary schools. Although we lived a carefree life, we also had very little. Our schools weren’t built well, our health system was not good either, but we were happy with what we had.

Now there are no gardens, no water, no playgrounds, nothing here in Shingal. I always think about this situation, how children are living their childhood while having no playgrounds to play in and no gardens to go to.

This was our house before we left

There were eight of us living there, my parents and we are six siblings. The house had three rooms at the back that mostly had collapsed. When we returned to Borek, we had to take it all down and rebuild a new one.

We don’t know whether it was destroyed by ISIS or because it was made of mud whether the weather and rain all those years affected it.

This is our new house. We barely managed the rebuilding as me and my siblings were all studying at school and university so it was hard for my father to do it all. He worked hard day and night so that we could get a good education. Three of us got scholarships to continue our studies and if it wasn’t for that, we wouldn’t have been able to continue our education.

The first time I visited the village after ISIS, was in 2016. I remember many of the houses had collapsed, the village was empty of people and the streets were very eery at night. The village looked very frightening. It was dangerous to go out at night. There was no electricity and you can hear only animal sounds and some cars.

This eeriness was an issue at night even before 2014. Yazidi people always felt it wasn’t safe for them to visit Mosul or Baghdad at night. Even other villages like Tel-Afar, which is a neighbouring village, was scary to visit too.

Before 2014 Yazidi people hardly left Shingal, unless they have a doctor’s appointment. For example, we have never seen Duhok, Erbil or Sulaymaniyah. I haven’t even seen Sinjar city centre. If someone said I will go to Duhok, it was like another world to us, we thought it’s very far away.

While we were away, we didn't think that we might go back again, but also, when we fled our village, we didn't think we would stay away all these years.

Bearing witness

The 3rd of August in 2014 was the day of our Eid. My parents, sister and I were working in our fields, but when we came home in the evening we realised that the situation was not good.

During that night we didn't sleep.

I could hear gunfire all around the village. I don't know from where, but north of our village there was a village called Khazuka, where Muslims are living. We heard that there was some fighting happening and that ISIS were there.

I remember, my father, went to the top of our house to the roof to have a look at what was happening. People were calling each other, each family had only one phone.

But in the morning we heard people say, nothing is happening, everything is fine. We thought that was it, the war is over.

Shortly after that we heard that people were fleeing from the village.

It was chaos. No one knew what was happening exactly. We didn't know where to go. What will happen to us?

Everyone was out on the street. Some big families from the village said they were going to Kurdistan. People were saying: "ISIS are coming, the war is not over".

We wondered what will ISIS do to us.

In our poor thinking, we thought that ISIS will come just to attack some military checkpoints or something like that.

But it wasn't like that.

We fled in this car.

We were three families at the back of this car, 20 people. My father and my uncle and two children were in the front, which was a space for only two people. We didn't take anything with us except our identity documents, some water, some vegetables and some bedding and that's it.

We didn't take any food, just water, and not even that much water.

We didn't think we would have such a long journey ahead of us. We thought we will just drive a little way away from the village maybe two or three hours, ISIS might come but after that we can go back to our homes, when they have gone. But unfortunately, it ended up years.

At first, the car wouldn't start. There was only a little bit of oil left in it. My father tried five times to start it, and then finally it started. We don't know how it worked, but we managed to flee!

Many people from the village were going towards the mountain, and we prepared ourselves to follow them.

But my brother, who was working in Sulaymaniyah at the time, called my father and told us not go via the mountain, instead we should continue straight to Kurdistan.

But we said no, all the people were going to the mountain. He said: "No, you will die if you go to the mountain. ISIS will come and they will kill all the people on the mountain. Just please come to Kurdistan".

One of my uncles and his family went via the mountain. My mother ran after him. She tried her best to stop him, but she couldn't reach him.

The road was crowded. No one was hearing anyone. People didn't know what was happening.

We fled via the border road, towards Kurdistan, via Rabia. I remember one of the roads was closed, and there were so many cars on the road. I remember there was a man from Khazuka, just north from of our village. He was a Muslim Arab, and he just opened the road for us and said: "Go!"

We stopped in Rabia. It was very crowded, and the cars were lined up one behind the other. There was no way to go forward, nor to go backwards. We were just stuck by the shopping centre outside Rabia, and the space was also narrow, something like five cars in a row were stopped. Wherever I looked back, I saw cars one behind the other, and the same was to the front of our car.

Then the gunfire started.

Bombs were coming from above us, and there was a man who was in the car in front, he told my mother to make the children sit down and to cover them. The gunfire continued for around half an hour, maybe more than that. We were stuck in that place. Noone knew what was happening.

There were Peshmerga soldiers and PPK soldiers. I thought they were coming from between the cars and on the sides. But they were just running, from all sides, and gunfire above us.

People were screaming.

I saw military cars, and soldiers, and behind one of the cars I saw a solider who had been shot and was bleeding, his head was hanging down out of the car onto the street, and someone was holding him. I think he was killed.

I looked elsewhere and there was another one also shot. These scenes are still stuck in my mind. The soldiers were also fleeing, they were running. They didn't fight, they were just going in front of us.

And then they opened the road, and we started to go forward. We didn’t know where we are going.

We just starting moving forward in the direction of Kurdistan and towards Duhok City.

From home to Kurdistan, my uncle was walking alongside the car and sometimes just following the car, there was no room for him in the car. My uncle's wife felt dizzy, she was vomiting all the time the whole way.

By this stage nobody had water or food, and we all were really thirsty.

This journey should normally take around two hours, but I remember we fled the house at around 10am and we arrived in Duhok City at 9pm.

And I remember there was a car that was driving along with us. They had a pregnant woman with them and they were pleading for any water. We had only one bottle of water, but we gave it to them.

We arrived to the border of Kurdistan with empty bottles. We had no water, so when we saw the river, we just started running.

People just got out of the car, and ran to the river to drink water.

Our car stopped just after we crossed the border, there was a village there called Derabun.

Along the way we have seen so many cars which broke down, some of them had no oil to continue, and noone was stopping for anyone, they just wanted to save their own lives. Some people were continuing on foot.

But there was one family they helped us in that village. They gave us water. And a bottle of oil to put in the car, and then we continued our way to go to Duhok.

On the road our car stopped again. We asked a man if there are any near places to get oil for the car, and he said, just go on a bit further, there is a village. We asked one of the children to run and check if there was any oil at this place but there was none. Then a car passing by, it was a Kurdish man, he gave us oil from his car, and we continue with that oil to Duhok City.

We arrived in Duhok at 9pm and my uncle was there. He told us that two families from our village’s were still stuck at the border in Rabia. They had to run from their cars. There was fire, there was war.

We couldn't understand what was happening around us.

In Duhok, I remember there was a young girl, she was around ten years old, she had come with people in their cars but she couldn't find her family. She was crying. She stayed with us for around three days until we found her family.

We stayed on the streets of Duhok for two nights, without shelter.

I remember a woman from Duhok who we sat in front of her house, said: "I have no space in my home to bring you in". She gave us a bottle of water and 2 glasses.

I have kept those two glasses to this day.

Some of our family went to Lalish as they heard that people were providing shelter there, and eventually after ten days, the Kurdistan region opened up schools to people for shelter. But the situation was unstable in Kurdistan too. Everyone was worried that ISIS will make it here too.

People were also fleeing from Sheikhan and from Sharya.

We thought, if Kurdistan will also end up invaded, what will we do?

We saw a few families from Sharya who told us they were going to Türkiye.

From all my relatives, we were the only family with passports. So we decided to go to Türkiye too.

I remember we stayed one night on the border between Türkiye and Zakho.

We arrived at 5pm and the border was closed. We remained there till 4am. It was very crowded. We stayed that night on the street.

After that they opened the border and people were just running. We entered Türkiye.

The driver who said will take us to a place inside Türkiye had our passports and at the border he had a fight with the border control officers. They threw our passports.

I remember my mother begging them to stop fighting as we just wanted to escape with our lives.

They stopped the fighting and checked our passports, and then we left. it was 6am.

We entered the village of Silopi which is the first village after the border crossing into Türkiye. We spent a day and night on the street. We were around ten families.

My sister and I were with my aunt’s family, my parents arrived two hours later. I don’t know what happened and why we weren’t with them. During all those four days we only had some water and biscuits, nothing else. I don’t think I slept for two days, hunger kept me awake. Then in Silopi, two men came and opened a small camp. First my mother was very reluctant to believe and trust them but we had no choice so we went with them.

There were around thirty small buildings with nothing in them. No water, nothing. Just a small shelter each. They opened them for us.

Later on, a large number of Yazidi families joined us and these small shelter buildings were not enough and very crowded so they put up large tents for people. They also brought us food and water.

We had no idea that we will be staying there for five months before returning back to Iraq.

We had no idea what was happening in Iraq, Kurdistan or even in Shingal during that time. Connection was cut off between us and our relatives and our people. We had one phone but sometimes there was no network to connect to others. We remained there between two to three months. They brought us a television which was installed in the middle of the camp, we watched the terrible scenes and what happened to our villages. It was beyond what we were expecting. We saw the killing and we saw people stranded in the mountain (emotion rising in her voice). I don't know how cameras reached them.

Thousands of people in the mountain, with no shelter, and no food. Some of them with no clothes, they had nothing. They were dying. We were watching and felt helpless. We were asking if people can help them. We even refused water and food, we just wanted people to go and help them.

Thousands of people died of thirst and hunger.

My maternal uncle’s family was there, too. They were taken by ISIS. We were still in Kurdistan, when they told my mother that her family was taken by ISIS. Two cars with ISIS fighters intercepted a five car convoy including my uncle’s just outside the village of Khanasor close to the border between Iraq and Syria. They rounded 72 Yazidis including my uncles and my grandmother just before they reached the mountain. My uncle’s wife was pregnant and she had to give birth between the hands of ISIS. They were going to take them to Mosul or somewhere but then the weather turned and a sand storm hit hard, no one was able to see anything. So my uncle turned the car towards the mountain and just drove, he couldn’t see where he was going but just needed to escape.

He was driving and wasn’t going to stop to check what happened to the other four cars and families left behind. ISIS started shooting at the car, he kept on driving, then when the dust had settled and they couldn’t hear any more bullets being fired at them, they discovered that the other four cars with the families have managed to escape too. They remained in the mountain for three months and then they managed to flee on foot to Syria and back into Iraq through Kurdistan.

In January 2015, we decided to return back to Iraq from the camp in Türkiye. My father said there is no future for us in Türkiye. We thought that we may have to find a way to go to Europe through Türkiye. There was a UN organisation there. They took all our papers and said they will help us reach Europe. Our papers are still with them, they said it may take eight years to get visas. So we decided to return to Kurdistan.

We went to Zakho, we stayed one day there, then we went to Misurike, a part of Simmel, near Duhok, with our relatives and stayed in a school.

We stayed there for around one week in the school building called Daliva school.

Every two families were sharing one classroom, all the people in the school were sharing the same bathrooms. There was one cooker only for the entire people staying in the school to make their food.

Here children are playing basketball in the school yard. You can see the shape of the school behind.

This is my uncle's family in their room. My two uncles shared one classroom. Each room was shared by two families along with all their belongings.

After that they created camps for us. Camps started appearing all around Kurdistan in Khanke, in Sharya, and they were taking people's names to send them to camps.

We came to Sharya camp – to these tents.

The camp was made of tents and roads only. We were sharing bathrooms with around 50 tents, bathrooms were in caravans. At the beginning of each row of tents there was a small bathtub filled with water and that was the water we used for everything.

Camp living and final return

We went back to our education. My brother went back to continue his studies in Erbil and then moved to Duhok University. He was doing English. The rest of the five of siblings went back to school. We lost one year because of what happened to us. But we all went back to school when they opened a school in the camp. It was a school with no chairs, no seats. We sat on the floor. I wish I had a picture of that time, but unfortunately, I don’t, because I had no phone at that time. I remember the school was made of three classrooms, we were around 100 students in one class made out of a big tent. There were only four teachers for the whole school. We continued like this for five months before desks and whiteboard were brought in.

My mother encouraged us to keep studying despite the state of the school. It is because of her that we are now all graduates.

We stayed in Sharya camp for seven years before returning to Shingal during the Coronavirus in 2021.

The camp life was hard, we had two tents, me and four of my siblings stayed in one tent and the rest were in the other. The tent was about four meters wide with our beddings, clothes and everything. It is also where we studied. I remember when I was studying for my end of year exams in my final year of secondary school, I was hearing children crying, the sound of televisions from different tents, and women speaking. I was hearing someone working and another washing dishes. All what is happening around me in all the tents, I could hear them all.

Another reason for going back to Shingal was the hot summer season claiming lots of tents to fires. Many tents burned and in fact even in the winter season, with heaters and electric wires tents used to catch up in flames and it burns really quickly.

We went back to Shingal during the Coronavirus. We stayed for one year in one of our relative's home because ours had collapsed. My father said we have to work to get money to rebuild the house. An NGO on the ground was helping people to rebuild their homes with some money. My father and brother worked to rebuild the house. Now it is finished we are living in it. We managed to rebuild the new one on the same land as the old one.