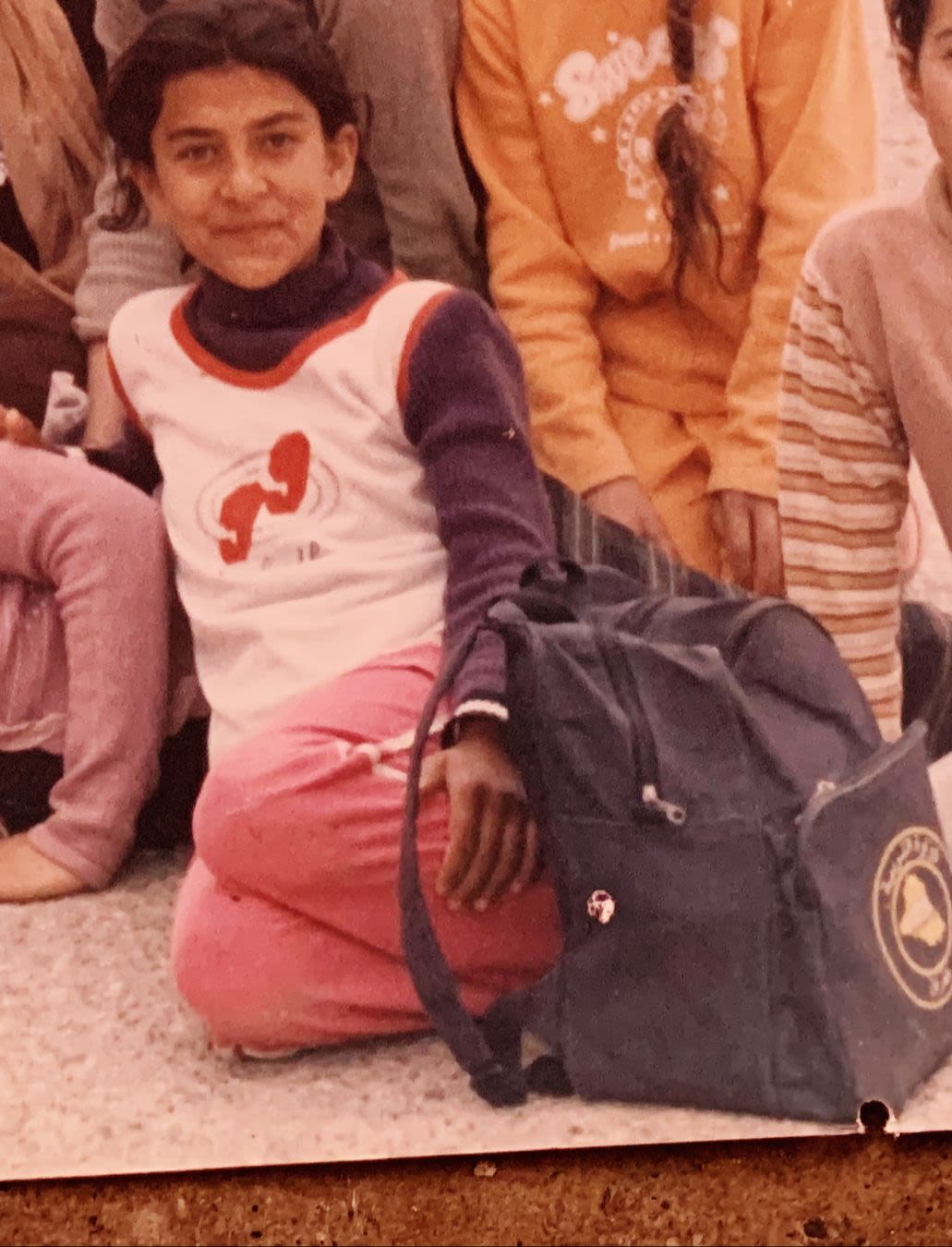

Faeza

The materiality of hope

My name is Faeza, I am 28 years old and currently studying for a degree in English Literature from the American University in Sulaymaniyah, for which I was awarded a scholarship. Before that I was working for a charity called Kashkool interviewing elderly Yazidis on events before 2014 for stories about the heritage of the Yazidi community as a conservation project. I was born in Syria and came back to Iraq in 2003 when I was seven years old. I am living now in Derabun .

Cultural heritage

I was born in Syria, we came back to Iraq in 2003 when I was seven years old. My parents had left Iraq because of the war and they decided to return to Shingal, to Khanasor, after the fall of the Saddam regime. Shingal is our homeland.

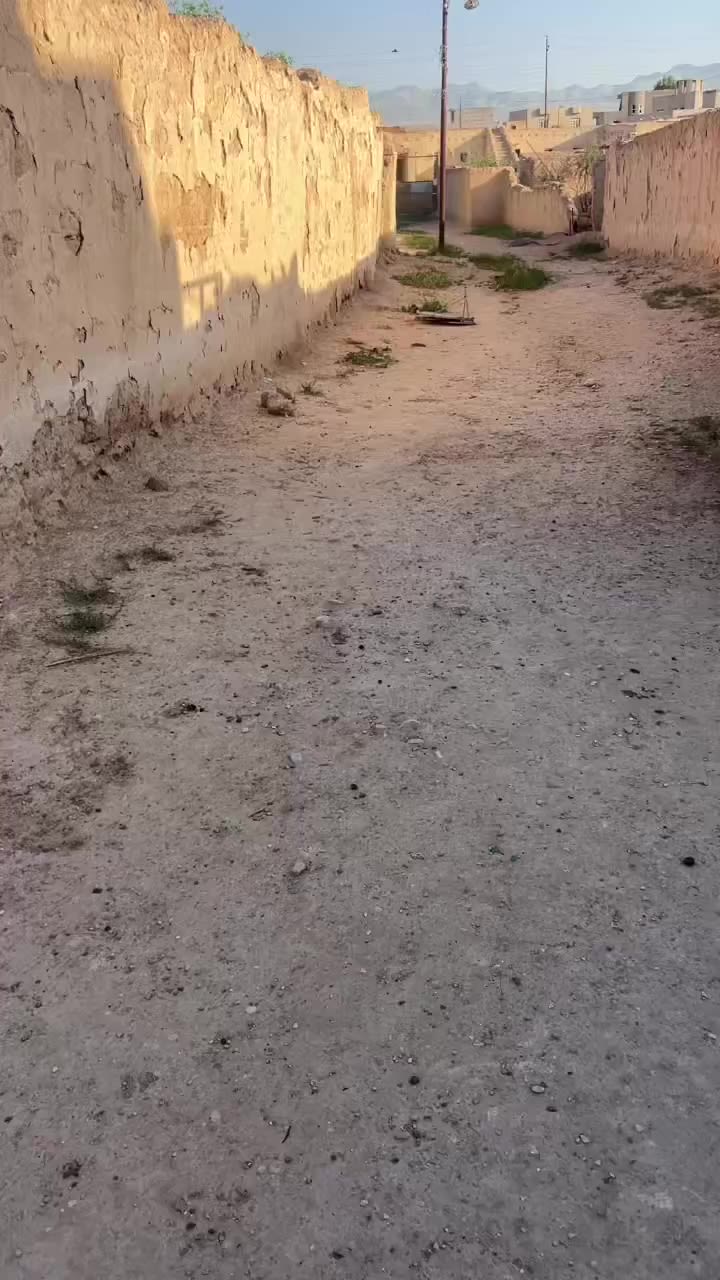

Khanasor is the largest complex in the north of Shingal. It is made out of two areas the old Khan (Khana) and the new Khan (Khana).

The new area contained houses for the population expansion of Yazidis, whenever someone gets married they move into the new area and build a new house.

Twenty years ago all houses were made of mud. Even the ones that were new. Around 2006/2007 blockwork and cement became more popular in new housing developments in the new khan.

The old Khan had narrow alleyways with mud houses while the new Khan had semi-paved streets and houses with more modern materials. The old Khan had very few main roads and most streets were narrow and they mostly just led to someone’s house.

We are ten in my family, my parents, five sisters and three brothers. Our old mud house was very small and the roof used to leak when it rained.

We had an old mud house with two rooms. People were very poor, we relied on agricultural farming and sheep.

Around 2006/2007 people wanted to improve their lives and we decided to build a house from bricks and cement.

Forced displacement

We stayed in Shingal till a month before 2014 events (referring to the Yazidi genocide).

I was in the middle of my final year of secondary school when the genocide in August 2014 took place. I was a teenager.

Shortly before ISIS came, we relocated to Derabun in Kurdistan. At first, we were not allowed to cross from Shingal into Kurdistan, because ISIS had control over Mosul and the situation was deteriorating. The Kurdish authorities were worried that opening the way into Kurdistan could mean that ISIS might come there too, but also they were probably not sure how many people Kurdistan could take in from the rest of Iraq.

We moved to a village called Derabun which is where we used to come to each summer for seasonal work, and then return in winter back to Shingal to attend schools.

We stayed there in an old house that belongs to one of my father’s friends, where we used to stay when we did the seasonal work before 2014.

This is also where we live now.

Derabun is a small village, there are Christians here as well as Yazidis.

Currently there are also tents housing Yazidis from Shingal who were displaced in 2014. But these are not official camps; those people who were placed in official camps across Kurdistan had their tarpaulin tents replaced sometimes but the tents in Derabun were never replaced. The camps also had food aid regularly distributed but people living here never had aid delivered to them. A few families who lived i in these tents returned, especially those who had a house back in Shingal, while others are still waiting for support to return.

Lots of families we know were killed in Rabia and Mosul on the hands of Daesh and we were scared. I was traumatised by the conditions around us and the number of people who started arriving to Derabun. It was a very difficult situation to witness family, relatives and people from your community coming towards the village suffered the worst events ever. People looked exhausted, half of their families were missing, you could see the suffering and trauma on their faces.

The people who were on the northern part of the Shingal Mountain escaped first, but the suffering and trauma of the Yazidis who lived in the south of the mountain was greater. They had to cross the mountain towards safety – which is not an easy task especially considering how high and how long the mountain is.

On the south side, the incline of the slope is slightly gradual and so its easier to climb up, but on the other side going down, it is really steep and much harder to come down. That is partly why many people were trapped for so long, and many of them were on foot, and walking for miles.

Lots of my family members managed to go abroad, they are in Germany.

My mother left in 2015 and I stayed with my father, my sister and brother at my father's friend's house in Derabun until 2017 when my father and sister went to Germany too.

Now from my entire family its only me and my sister here in Derabun and another sibling in Sharya.

I returned to Singal in summer 2017, We stayed for only fifteen days, life was near impossible in Khanasor.

Khanasor

Khanasor

There was no electricity and there were virtually no houses, most were either demolished or eroded and weathered. So we decided to move to Snuny and we stayed there for about a year and then eventually went back to Derabun.

About two years ago (2022), we attempted to leave Iraq. We wanted to attempt to reach Greece, and then onwards to Germany. For me it was like an adventure. I left with my sister and several other people, relatives we knew.

We went through Ibrahim Al-Khalil to a place called Cizre in Türkiye. We entered Türkiye with our passports as tourists and took a bus to Istanbul.

When we were in Istanbul, a guy got in touch who helps people make these crossings, he took us to a hotel. For two days he kept on texting us saying that we will leave in an hour, but it did not happen because the route was not clear or something.

Then they took us through Istanbul walking with all our luggage and food until we reached a deserted area in Istanbul that looked at a film set for a mafia movie. There was no electricity and no other amenities and no people. There were only a few people on the road selling things. But then we realised that they were part of the smuggling operation, inserted in the context of the area to keep a watch.

They took us to a building, it was very dark, there were no lights. They told us not to use the flash on our mobile phones either. We felt scared, we were five of us, my sister and I and three other friends, two men and one woman. The building was full of Afghanis, and other nationalities. We spent from 10pm till 3am in that building in one room which had a cat and a mouse and the cat was playing with the mouse. I was petrified. There were other people in that room, and slowly we discovered that there was another group of five Yazidis there too but we couldn’t see well enough to recognise anyone. They approached us after they heard us speaking in Kurmanji. We felt a little safer with them, then there were ten of us.

Later on, another seven entered the room and they also turned out to be Yazidi. One of them was an older man, 40 or 45 years old with his wife and children, so we felt safer when we saw them. At around 3am they ushered us downstairs. They put 26 of us in a van and drove us to the border between Türkiye and Greece, the journey took five hours.

We were sitting nearly on top of each other in that van, it was so crammed, and we had to duck our heads down all the way to avoid getting caught by the border guards.

The Turkish guards saw us, took photos and then told us to continue. Without their help, we wouldn’t have been able to make the crossing into Greece.

It took a whole day through the forest to reach the crossing to Greece’s forests, but we had to cross a body of water and they provided dinghies for us.

We were about 40 people, 26 of us were Yazidis. The smugglers were with us. They needed a phone for GPS tracking, so I volunteered mine. I told him whenever my parents send messages for him to respond sending our GPS location. We managed to communicate in English with him. I knew some English then. My other sister in France was managing to contact us.

We walked for hours through forests, mountain, a wire barrier and people were falling, got hurt and so on. We stayed five days in the forest in Greece. The journey was incredibly difficult. People who did the same journey encouraged us saying it was easy, but they probably said this so as to not scare us. I got sick on the road. I was not able to eat. The five days we spent in the forest I was only able to drink water. It rained on us; we were sleeping in the forest on the ground with no bedding. We were not thinking of the possibility of being attacked by wild animals or insects.

We were not thinking of anything other than our goal destination, Germany via the refugee camp in Greece. My family were already in Germany.

We ran out of food and water and the smugglers told us that they were going to leave us there. We decided to continue on our own, but then the Greek authorities caught us. That was the first time in this journey that I felt paralysed with sheer fear. We were told that the Greek border control had been taking people’s shoes, jackets and money so I panicked. But they just drove us back to the Turkish border.

So basically this whole failed attempt at leaving ended up being one day of walking to get to the forests in Greece, five days in the forest, then one day coming back. On the Turkish border there is a prison camp for those who get caught either trying to leave Türkiye or those who get returned back to Türkiye from Greece. We ended up spending another five days in that prison camp in Türkiye.

They took our names and finger prints and then drove us back to Iraq on a bus through Ibrahim Al-Khalil road. The journey was exhausting and I don’t like to get into the details.

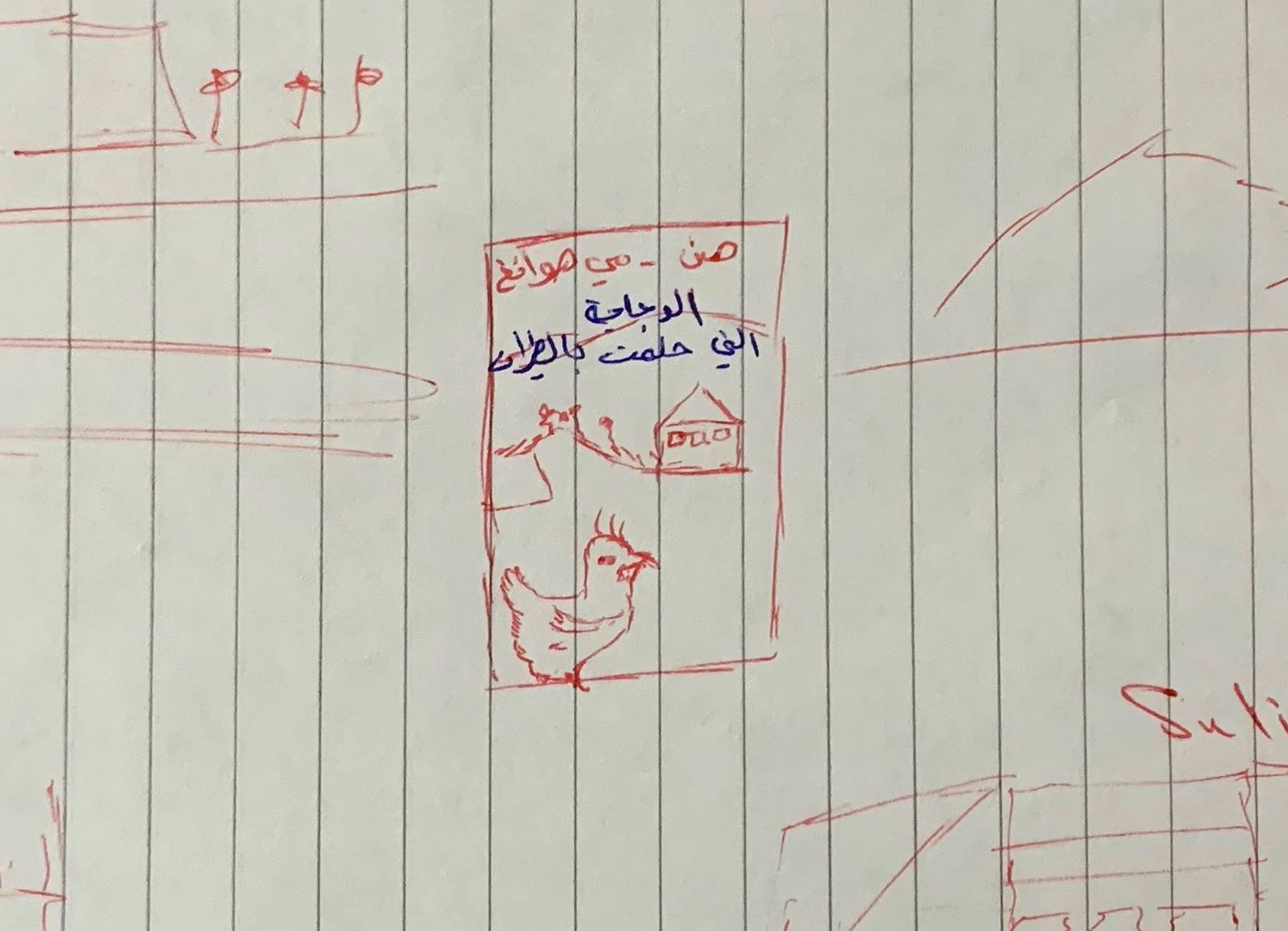

A dream of flight

If you have asked me a year ago, I would have said I would like to live outside Iraq, but now I feel I am forced to imagine a life only inside Shingal. I have tried and failed on several attempts to leave the country. My family left Iraq nine years ago, and I have been trying to leave ever since.

I have tried to get out by signing up for an English course, but that attempt failed. My parents put a case for family reunion, but that failed too and then I tried to leave through Türkiye and Greece and that didn’t work either.

So now, since I started university, I have started feeling that I am getting used to the situation that I am in and the reality of living in Iraq. I am also witnessing lots of people returning to Shingal.

There is a place in Lalish on the mountain, when I go there I forget everything and I feel safe and at one with this place.

Lalish connects directly to my heritage and belonging to this place. I will certainly long for this place if I ever make it abroad one day.