Noori

Reaching beyond the borders of my universe

My name is Noori, I am a self-educated filmmaker, script writer, photographer and advocate for the Yazidi cause. I am 28 years old and have been volunteering and teaching across different NGOs in Sinjar. I have also contributed to the suite of training offered by Sinjar Academy (and some of the participants in this project have attended my workshops). I am originally from a village to the west of Khanasor where I was born and grew up, and I have returned to Khanasor but to a neighbouring village to the one I was born in. I enjoy reading and exploring new knowledge. Although I was born to a poor family, with limited resources, I made the most of what I had to fulfil my love of photography. In 2016, I got a new mobile and started taking photos. I fell in love with photography, and discovered it as a way to tell the stories of the Yazidi community.

The minute you step outside of my village, there is nothing, there is only an open landscape that leads to the border between Iraq and Syria. I used to ask myself looking at the distance, I wonder what is there in the distance? Does the world extend beyond the point that I can see? I used to keep telling myself, I am sure there isn’t. That is it. This is life, the world and everything there is. I used to feel that this is also where the world ends with the borders of my village. I feel this concept runs true with a lot of other people who lived in my village.

We lived a simple, and spontaneous life. We had simple dreams that were confined by the borders of the village

Until 2010, we had no internet or mobile phones, but then they became more widely used, as well as social media, I had a Facebook account from 2010. But to some extent, we did not even know how to use social media as a tool, not even mobile phones.

More than a walk

I would like to start my story with what happened a few months before the genocide. It was the 26th of March 2014. This was the story I told with my map drawing in the workshops we did for phase 1 of the Ruptured Atlas project.

This story is very much connected to this question I always had, which is: where are the world’s borders?

I was with four or maybe five of my friends, we were around 17 or 18 at the time.

We went up the mountain (Sinjar Mountain) heading towards Sheikh Mand temple, meaning "the protector". We usually go there when there is a religious event or Eid or any celebration.

We headed to the mountain on foot. It is about one and a half to two hours walk, we had taken with us things to sit on and some food.

There was a man, who we couldn’t identify, walking behind us. With our teenager ways of thinking , we all thought he was following us and what are we going to do about it? We decided to walk slowly so that he can pass us by. Luckily he was just minding his own business.

All the roads up to that point are predominantly created for cars. But we decided to walk instead of getting in a car. We wanted to take in the nature. It is beautiful around there.

We reached a big rock which is where we decided to sit and rest

We decided to get our picnic out. We were all Yazidi boys who were raised to believe in the Yazidi faith, but one of our friends had a little bit more faith than us. We were preparing the food (here on the map you see I drew a saltshaker), and we ran out of salt. So we started looking everywhere for salt, then that friend of ours who had more faith than us, found a plastic bag with salt inside. This is what a lot of people did, when they finish from their picnic but have leftover of water or anything useful, they used to bury it around just in case someone else need it in the future. He said to us, see if you have a clear conscience you get what you are looking for.

I have mentioned this incident so that I will set the scene for the 3rd of August 2014. Just before that, the World Cup was on, I think Germany won. We were also following the news on the development in Syria and the ISIS invasion of other areas around us. We used to gather together to analyse, to plan, to predict what’s happening and what’s to come. We were all on edge and very anxious.

We were going about as normal but we were all on edge and worried about the situation. There was one person from our village who was in Badush prison (in Nineveh Governorate near Mosul). When Daesh (ISIS) invaded Iraq, the prisons were opened and people ran away. When he got back to our village, he told everyone how Daesh had a blood thirst driven ideology. He raised our anxiety and everyone started deliberating what to do.

On the day

On the 3rd of August, we woke up in the morning, it was nearly normal, but we knew about the massacre that had taken place in the south of the mountain. It was around 8:30am and we were still deliberating about what to do. At the time, I had a Facebook account, so I decided to contact a friend of mine who was in Gohbal (a residential complex to the east of the Mountain, in Snuny). I asked him what’s happening there, he said they were fleeing the complex and he was advising us to flee too, there is no hope he said. At 9:20am, I posted on Facebook that we are leaving too. About 9:30am we decided to leave. We had no car. It was us (the family) and my uncles and cousins, all went on foot heading towards the mountain. We had very little on us, supply for one day perhaps. We thought we will be out for one day and then we can return. Once we crossed over the last road in the village, there is a main road and after that it is empty landscape between there and the mountain.

As we were crossing the road that sits between the village and the mountain, I saw the army that was withdrawing. One of them was on a military vehicle who passed by us and he shouted, run, escape with your life, they (Daesh) are headed towards you. I felt petrified and let down by this incident that I will never forget, how come someone who has the capacity to defend civilians, runs away and leaves them to their assassins (Daesh).

We headed towards Sheikh Mand temple and we saw a large number of people, some on foot and others in cars filled to their rims with people. I went with my sister and other relatives, we ended up sitting in a small patch of land that my family used for farming. We saw waves of people heading towards us.

We spent the night and day in the mountain and we knew we couldn't return just yet because those who left after us told us that it is still not safe to return.

Sinjar mountain is one big mountain with a dip that is like a wide flat valley and then another smaller mountain parallel to the main one. There are several passes that act as entrances to the mountain. Towards Sheikh Mand temple, there is a pass wide enough for one car to pass through. Men were taking shifts to protect this entrance. The north side of the mountain has more temples so many of the people fleeing from all over Sinjar region were heading there.

The genocide took place in the hottest month of the year in Iraq especially in the morning and afternoon. But at night, the temperature plummets down. We had not come prepared with covers and blankets. I had a piece of cardboard, I took it and found a corner in the deserted land to shelter.

But we struggled in the middle of the night as temperatures plummeted further, my uncle suggested that we dig a hole in the ground and cover ourselves to get some warmth. It was like we were digging our own graves. We could only sleep from exhaustion. We were around 40 people, all relatives. We remained there for a week.

We ran out of food. People who brought their sheep with them started giving out their sheep for people to cook and eat. We had wheat which we boiled and ate. There was very small well that belonged to a local family (Avdi’s Family), without their help we would have died from thirst.

Despite the hardship people helped each other. Especially those who came from the south of the mountain who had far worse experiences than we had. They needed more help especially their children and elderly. There are so many incidents and desperate decisions that people had to make. Rumours of ISIS progressing into the mountain used to send more anxiety in people.

After a week, we started to see humanitarian helicopters dropping aid. Despite this, lots of people died. The food parcels were hitting the rocks on the mountain and shattering, bottles of water were braking into pieces. We were near two temples close to one another, Sheikh Mand and Amadin. Behind these two temples, there is a flat piece of land. We lit fire there to create more of an even flat surface to allow helicopters to drop aid supplies there.

What struck me is that I think people had no comprehension of what was happening. I think people lost their logical thinking ability. They were all traumatised. The minute they heard the helicopter hovering on top of that patch of land, everyone runs towards the helicopter and then aid can’t be dropped because otherwise it will squash people. Helicopters were trying their best to send messages to the people to stop them from running towards it but people were desperate.

I often wonder now, even though I was 18 years old, young and healthy, but I am struggling sometimes to remember what happened precisely. Probably my mind has masked the trauma to protect me.

I remember during the first seven days, even though I had a mobile, I did not take any photos. I wonder why? I remember my cousin and I were sitting under a tree during those seven days and we were just watching what people were doing and reactions to certain things happening. I even remember that my phone was playing music.

Reflecting back on it now, I wonder what was going on in my head to make me do what I was doing. My only explanation to such behaviour is that we were not anticipating nor expecting what was really happening to us.

A while ago, since my return, I decided to go and visit that exact same spot that we fled to and I documented the location properly with photos and video clips. Before this project (Ruptured Atlas), I decided to write about what happened but I was struggling to remember some of the details although I can still remember the route and the ways we have taken through. I recall fragments of story, but it feels to me that it is very disjointed.

On the 7th day we saw three Kurdish guerilla fighters who were based in the mountain who said they will open the route towards Kurdistan and Syria and then back into Kurdistan region in Iraq.

There were lots of discussions and deliberations, people were scared to leave the mountain and venture elsewhere. But slowly people started leaving because there was no other option available. There were about 35,000 people trapped in the mountain, which is about six or seven villages in full with their clans.

When they opened the route for us, slowly but surely people started leaving the mountain heading towards Kurdistan. We saw lots of cars and people walking. There were lots of children on the side of the road crying, no one knows where their parents are, elderly people too were on the side of the road. When cars passed by and we see they had lots of bedding, people stopped it and swapped walking people and children with bedding and so on. I remember on that day we walked for eight straight hours, we only stopped when we found a farm along the way to pick up a few things to eat.

I recall walking on my own, I don’t think I stopped to check where my family were. I was carrying a bottle of water; from the heat the water was so hot it didn’t feel nourishing to drink from it. I also gave small children and women some of that water.

We just needed to reach the border which was about two hours walk away. I remember seeing people lying on the side of the road who couldn’t walk anymore. Cars that were passing by were so overloaded, even on the roof of the car people were hanging for their dear life.

When we crossed the Iraqi-Syrian border there were big water tanks and I saw lots of people filling up their bottles and containers and continued to walk, although there were people who were getting water and returning back for their family and relatives, but I didn’t look back. I felt slight relief.

There were trucks that belong to People’s Defence Units (YPG) who came to help people who couldn’t walk anymore. They took them from the border and into the crossing back into Kurdistan Iraq. But when we got there it was night and it was not safe to cross back into Iraq. So my family and I had to get onto one of the trucks to be taken into Kurdistan.

There were tens of trucks full of food and supplies as well as people. Those who had their own cars were passing us by and people like us without cars had to wait for the trucks to take us into Iraq. No one was allowed to just walk across the border into Kurdistan Iraq. At that crossing into Kurdistan, people started checking on each other as if they have started to understand what was going on and the events of what’s happened started to sink in.

At night the cold weather prevented us from sleeping. We were given blankets but they weren’t enough so we decided to put a camp fire on and people sat around unable to sleep. I started checking on my family. I found them all ok.

The trucks took us to Simmel near Duhok, near Sharya, which is where our camp ended up being.

When we got to Simmel, they took us to a school building. It was a two story building, each story with four classrooms, each classroom housed about two or three families. There were so many of us in one building. It was very difficult to live like this with close proximity to other families you might not know that well.

In that school, we sort of agreed amongst ourselves, that the young men will sleep outside in the school yard and women and children and elderly sleep in the classrooms. We stayed there for three months.

It was a very difficult time. Nevertheless, when we arrived in Simmel, we felt much better.

I really liked Simmel. It was quiet and calm and the local people looked after us. The majority of people in Simmel are Kurdish and there were also Christians and very few Yazidis. There was a Mosque nearby where the Imam announced in the loud speaker for locals to look after us as much as they can and donate whatever they can. He said, “Help and look after your brothers. They (Yazidis) are people of your country too”.

I don’t think once I heard this word that tend to disturb Yazidis (without mentioning it).

We used to receive food through the Barazani Charity Foundation (BCF) because there was nowhere to cook in the school. The school’s bathrooms were turned into separate bathrooms for men and women. After that, people started leaving the school to find better places to live. Men started finding day labour jobs.

I recall an incident that I will never forget, because of the crowdedness inside the classrooms, I spent the majority of my time outside the school gate. Just sitting there contemplating life.

A really nice car stopped by with a middle-aged man driving, he lowered the window and asked if I was exhausted, I said yes, so he said: "Get in the car with me". I got in the car without thinking. He took me to his house and asked his wife to bring me fresh clothes. He mentioned a name, I can’t remember but it sounded like he was speaking about his son, and he directed me to the bathroom. It was not only my first experience leaving my village and going into a city, but also to see the bathroom was so big and had a shower. I took a shower and wore the fresh clothes. I got out of the shower and they invited me into their dining table which was like a picture, filled with all kinds of food. I saw the food and didn’t know what to do. I ate a bit, I wasn’t hungry but he kept on asking if I would like to eat more. When I said I am satisfied, he said, he will take me back. He gave me a bag with some clothes and other items and took me back to the school.

Until now, I have no idea who he is. I don’t think he said and I don’t remember asking and I don’t remember where he lives either. The only question I remember he asked me was: "Are you one of the forcibly displaced people?" I said, yes. Until this day I remember this incident. He was super kind Kurdish man.

Looking back

&

Looking forwards

During this time we started questioning ourselves about certain behaviours that we did. The trauma and emotion were too high to be able to process what was happening to us.

They took us to Sharya camp. My family is still there till this day. My younger brothers are studying and our home is not fit to go back to. But I am not living with them right now.

As you know, the Yazidi people are from a conservative background, in terms of following both Iraqi as well as Yazidi customs and traditions .

Their faith is really important to them. You have probably seen the red and white yarn bracelet that a lot of Yazidis wear all the time. We have special prayers which I used to recite them frequently. But one incident happened to me that shock all that belief. When we were leaving the mountain (on the seventh day), people were going down towards the temple, pray and walk on. I followed my family and headed to do the same. I faced the temple and just at the entrance, I stood watching the horror on people’s faces as they were praying for protection. Even my family, my sisters were doing the same. Something changed inside me. I questioned myself, why do I believe in this. I didn’t enter. I felt that I lost that belief there and then. I felt this was a huge transformation in my life.

The years that I spent in Sharya camp, I was reading and getting to know the world and reach beyond the borders of those beliefs and that small village that was my entire universe. I stopped embracing the constraints of the religious believes. Because of leaving school in 2013, I felt that I should pursue what I really want and value in life. So I began attending courses and training to develop myself because the limits and borders of the world that I imagined I was part of disappeared.

In 2016, I was helping my uncle in his farm in Faysh Khabur, his children were all at school, but I wasn’t, I had a mobile then and I started taking photos of that beautiful landscape. That moment made me realise my love of photography. So I started looking for training courses to help me develop my photographic skills. I find that there is a deficient in supporting the creative sector in Iraq for the sake of creativity, the majority of the training courses that had some photographic skills were for journalists. I started working in journalism, I found a love for writing too. So I returned to Sinjar to do documentaries. In 2017, I had three cameras. I learned English and furthered my cinematic skills and photography all through self-education. But I still wasn’t completely aware of the power of creating, documenting and archiving.

Since that time, I started questioning myself, do I stay in the camps, do I go back to Sinjar, or should I leave the country. I continued to work for NGOs and charities and other organisations as a volunteer. I grew the love of reading in me. The more I read, the more I question myself, what’s next for me. I felt that reading opened my mind to questions that were problematic to the conservative way of thinking that the Yazidi community practices. I co-organised a book festival in Lalish. I ran critical thinking discussions about life, religious believes, education, love and marriage, and so on. I was doing all of this while I was still in the camp, until 2017/18 before I returned to Sinjar. I only visited Sinjar during that period when my family used to come to visit the mass graves.

Between 2017 and 2019, I was in a difficult mental state. I was questioning myself and my life choices, why have I stopped studying, why haven’t I left Iraq to live abroad, why haven’t I got a house of my own or a stable job. I had a rush of anxiety. I began to question everything, not just religion, politics and my life choices, but everything. These feelings were compounded by the state of Sinjar and the level of destruction. I felt helpless and thought people will never return to this state and the people who have returned look like they are living a temporary life. This is also because people were scared of what might happen, and whether the genocide might happen again. I feel people were living on the fringes of life itself. I started writing but also I started working in advocacy, I have always been active in speaking up about injustices and also encouraging the youth to think critically about their future.

Home?

In 2019, I decided to come back to Sinjar. Life in the camp was very difficult and I couldn’t bare it anymore. I had no privacy there. So I headed to downtown Sinjar. It was the first time I visit after ten years. I had no plan but I felt this urge to return. I wanted to spend all my energy in Sinjar even if one day I will leave, I wanted to do as much as possible for Sinjar before that. I started working for a local organisation as a media officer and then I worked as a journalist for several other organisations.

I remained in the centre of Sinjar, for two years, then the Coronavirus hit and I ended up staying longer. I actually benefited from that time during the pandemic. I developed myself further but also because I was a photojournalist I was allowed to leave my house so lockdown did not affect me as much. Although that time, I was proud of how I was supporting myself mentally, financially and looking after my flat, washing my own clothes and so on.

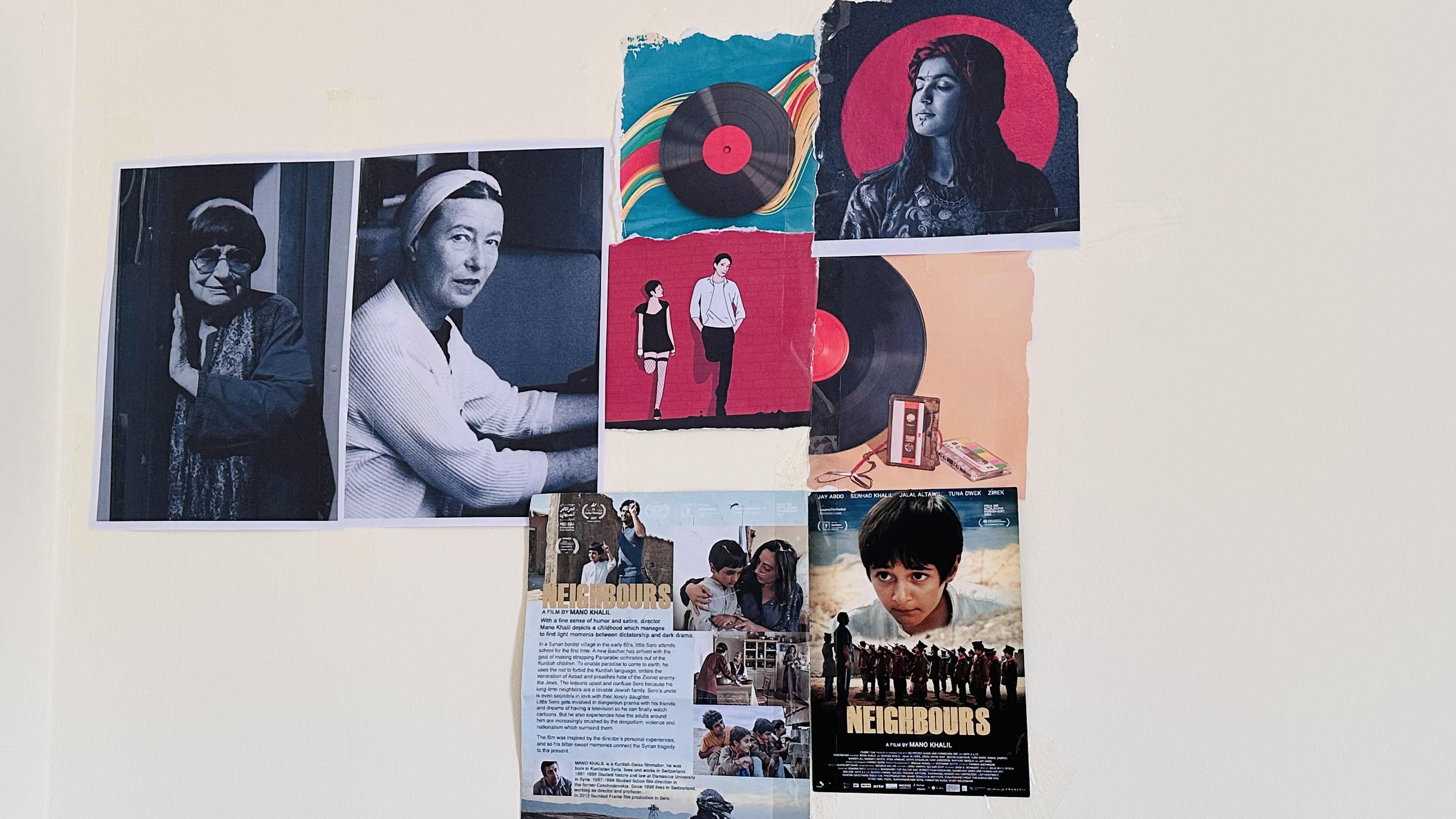

Every time I rent a room somewhere, I slowly start to make it my own with posters and hand sketches, feel at peace, the landlord asks me to leave because of one reason or another, wanting to sell, wants to live in the house himself or wants to raise the rent. I take everything and try to find somewhere else and the journey starts all over again. Two weeks ago the same happened again, so I am now staying at my aunt’s house.

I have two families, one is my biological family and the other is my mother’s family which is where I grew up and was raised. So I have a family in Sharya camp and I also have a family in Sinjar at my maternal uncle’s house. Because I keep hopping from one place to another, I now have several bottles of the same shampoo in each and every place. I forget to collect them when I leave.

A while ago my family in Sharya camp said they wanted to go back so I went to check our old house. It is completely impossible to restore besides I have no financial means to rebuild it a new for them to return. Such incidents remind me that I have not healed completely from the genocide. Possibly will never heal until some geographical and mental stability return to our lives.

It has been 10 years, I don’t feel there is a place of my own that I would go to work and come back to. I have a small cactus plant that I bought in 2021, it has been with me ever since. I feel if that plant can speak, it would have said: "Be patient, stay in one place!" Every so often I move and I take the plant with me. I feel tired of trying to find this place, my own place.

Mental Health

In 2021, my mental health deteriorated, my father died, I also went through a rough patch with a romantic breakdown and had a fire accident. In our society, speaking about mental health is a taboo. People don’t want to talk about it. But I was always very open with my feelings and I encourage other men to be connected with their emotions more. At that time, I thought I can’t preach but don’t allow myself the time and space to really heal. So I decided to seek therapy sessions (for six months). I can’t believe that with all what happened to us, people still don’t want to talk about the genocide and what happened to them. I felt I owe it to Noori the 18 years old back then, for the Noori who is 28 years old now to allow the healing to take place. These mental health sessions helped me immensely.

This period of time has helped me find and express myself, and has also helped me to discover and learn more about my passion for cinematography and writing. I think these forms of creativity are a way to begin to heal from the atrocities of genocide inflicted on my people. I produced a short film that I am proud of called: Lonely Hands, which explored the feeling inside me that I was going through and the judgement of mental health within our society. Cinema is scarce in Iraq especially films that explore the critique of societal struggles. I feel this is my niche and I want to develop this. I felt the cathartic healing in cinema making. I was not only expressing my own struggles but also projecting community and society’s struggles too. So filmmaking became my preferred medium of expression. As a person, at this moment in time, I feel I found closure from the trauma of genocide, but not complete healing.

In early 2023, I had an idea to establish a community of photographers, filmmakers and cinematographers. There was a call by Sinjar Academy for photography and filmmaking training which I applied for and accepted after a selection process. Through that, we kept in touch with a group of us who have shared interests in these forms of creative practices and we found nuances in those who are more interested in writing and others who are interested in the technical aspects.

We also collaborated on three films, Sinjar Academy published a couple and I published the third on a webpage that I have created and called it Sinjar Film School for studying and making films. So I started developing this idea, especially to create a platform from which I can develop a community interested in filmmaking and cinema in Sinjar. In June 2023, we began a Cinema Club where we would watch films online on our own and then we gather online to discuss the films we watched. In August, we decided to run a Cinema Club live on-site at Bait Al-Taayesh (House of coexistence), in Snuny where we would screen films outside in the open air, and when winter came and the weather got colder so we decided to run the evenings from inside the house. We then got busy with work and other life commitments so we took a break and then in March 2024 we opened the club again as part of Sinjar Film School. I want for this club to be the central hub for all those who are passionate about film and cinema to gather and discuss and develop skills. In addition to that, I feel that Sinjar has so many untold stories that we need to tell to make the world hear us. I want us to tell these stories the way I want the world to hear them, the way we see ourselves, our identity, our language. I didn’t want people to come here to document our lives and then go to tell our story on our behalf. I started this initiative as a form of recovery, a form of healing that follows post-genocide time. This is the way I was able to express myself. I saw Sinjar Film School as a mini-school a small initiative from which opens up a big window into our creativity here in Sinjar. We now screen films at Mirzo Training Centre for Music, which is a famous entity and band here in Sinjar, which I am a member of; this is one of the paths I see for myself and others towards healing.

I don’t think I have ever felt the true meaning of stability. Not even when I cast my vision back to the days before 2014 and even to my childhood, something always felt slightly disturbed whether through the poor difficult way of life we used to live or the events that conditioned us.

At this moment in time, I have the urge to study abroad. I want to study cinematography and filmmaking and screenwriting. These programmes do not exist here in Iraq now.

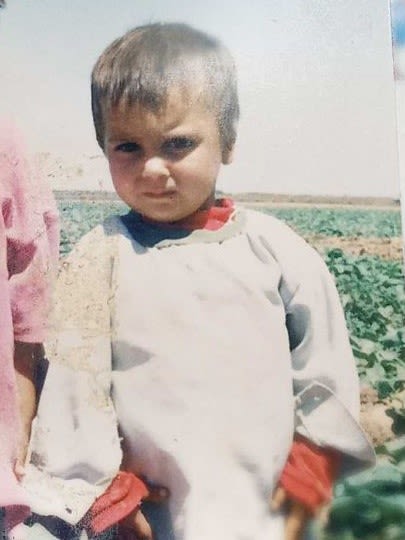

But eventually I want to return. I want a home in Iraq. I feel this is my homeland and I will never go out and not return. But I want serious assurances that what happened to us, Yazidis, will never happen again. I want to enjoy life, I want my cactus plant to be with me all the time here in a home in Sinjar. I want my childhood photo to be placed in the hallway by the stairs. I want stability for my future and my past.